A panel of industry analysts Wednesday presented their estimates of how much the Inflation Reduction Act would reduce greenhouse gas emissions and its impact on average household energy costs.

The webinar hosted by Resources for the Future (RFF) came as the House of Representatives prepares to vote on the bill and its $369.75 billion in clean energy funding, which the Senate passed on Sunday. (See Senate Passes Inflation Reduction Act.)

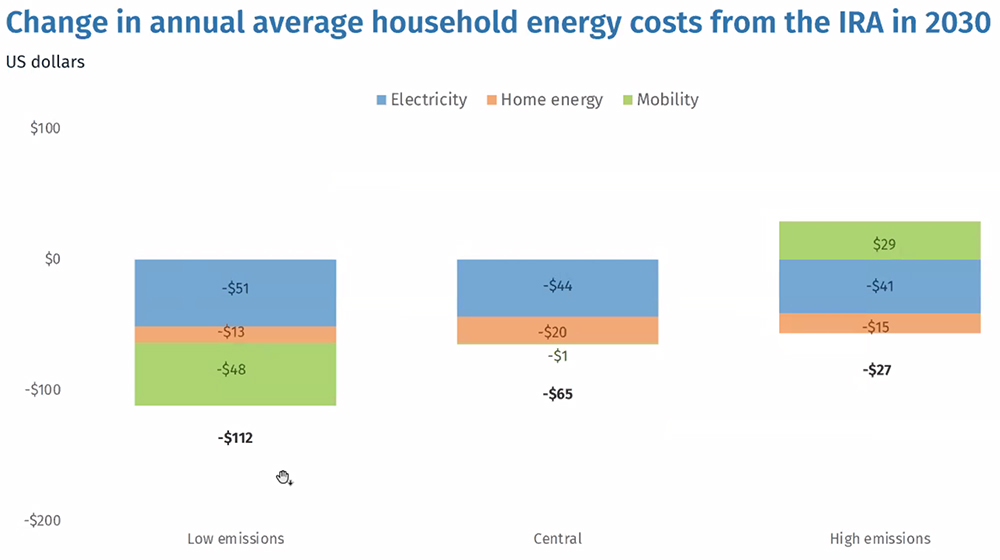

Rhodium Group found that the average household savings from the IRA would run from a low of $27 per year to a high of $112 per year, depending on natural gas prices.

Rhodium Group estimates the IRA will produce modest home energy bill savings for the average American household. | Rhodium Group

Rhodium Group estimates the IRA will produce modest home energy bill savings for the average American household. | Rhodium Group

RFF’s own analysis of the bill forecasts a 5 to 7% cut in retail electricity prices by 2030, which could translate to per kilowatt-hour savings of about a half to one-and-a-half cents by 2030, again depending on natural gas prices.

“Between low and high natural gas prices, there’s roughly a swing of about over 10% in terms of retail electricity prices,” said Kevin Rennert, RFF’s director of federal climate policy.

But, he said, “having the IRA in place — and the clean electricity that is driven by the policy and incentives — actually reduces the effects of variability within natural gas. … Having more electricity on the grid certainly insulates you against price shocks.”

While they differed on details, all the speakers at the webinar agreed that their respective modeling programs found the IRA will provide energy savings across a range of variables. They also agreed that however sophisticated their software, some aspects of the bill would be hard to quantify.

Jesse Jenkins, head of Princeton University’s Zero carbon Energy systems Research and Optimization (ZERO) Laboratory, pointed to siting constraints for solar, wind and carbon capture projects. Examples include “the ability to scale up the workforce to deploy resources at this scale and the ability to expand networks like transmission and CO2 pipelines and storage to support this level of growth,” he said.

Clean Energy Incentives

In addition to natural gas prices, RFF’s analysis also factored in the potential clean energy incentives contained in the IRA, resulting in different scenarios with base and bonus levels of incentives. For example, the bill’s proposed technology-neutral clean energy investment tax credit (ITC), beginning in 2025, has a base of 6% of projects costs, but can be multiplied by five, to 30%, for meeting certain prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements. (See What’s in the Inflation Reduction Act, Part 1.)

The technology-neutral incentives are “a big deal because it no longer will require an act of Congress for a new technology to be eligible for these credits,” Rennert said.

Another plus: the bonuses are “stackable” so that a single project can receive multiple bonus incentives, such as a bonus for meeting the prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirement and a second for project location in an “energy community” affected by the closure of a fossil fuel plant.

With such stackable bonuses, a project could earn a 50% ITC, Rennert said, and help slash GHG emissions from the power sector by as much as 75% — or an additional 4 billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions — below 2005 levels.

The ZERO Lab analysis also said the IRA’s clean energy incentives would cut power sector emissions 75% but pegged cumulative GHG emission reductions at 6.3 billion tons by 2030.

“The bill primarily reduces emissions by making clean energy cheaper,” Jenkins said. “It’s about making it cheaper and easier for businesses, for utilities, for households, for everyone across America to adopt cleaner energy sources, to make more efficient choices about upgrades to their businesses or homes and to electrify energy consumption in buildings and transportation.”

The law “could spur record-breaking growth in wind and solar capacity” depending on “how fast we can grow and continue smashing records each year,” he said.

While the U.S. added 15 GW of wind and 10 GW of solar in 2020, the ZERO Lab analysis shows the IRA more than doubling wind to 39 GW by 2030 and increasing solar almost fivefold to 49 GW.

Jenkins also sees the bill’s clean energy incentives having a ripple effect, making it “easier and cheaper for states or cities or companies at any level across the country to increase their climate ambitions. It also reinforces the economic benefits of any future federal regulations,” he said.

Oil and Gas Leasing

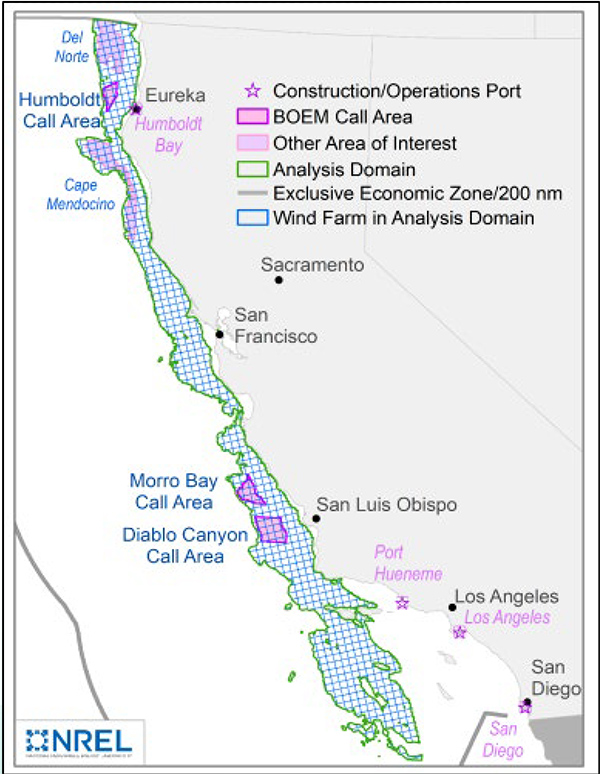

Both Rennert and Robbie Orvis, senior director of energy policy design at industry consultants Energy Innovation (EI), looked at the potential increase in GHG emissions that could be caused by the IRA’s oil and gas leasing provisions. The bill requires the Department of the Interior to complete stalled oil and gas leasing auctions in the Gulf of Mexico and off the coast of Alaska.

At Wednesday’s webinar on IRA impacts were (clockwise from top left) moderator Karen Palmer, Resources for the Future; Kevin Rennert, RFF; Robbie Orvis, Energy Innovation; John Larsen, Rhodium Group; and Jesse Jenkins, Princeton ZERO Lab. | Resources for the Future

At Wednesday’s webinar on IRA impacts were (clockwise from top left) moderator Karen Palmer, Resources for the Future; Kevin Rennert, RFF; Robbie Orvis, Energy Innovation; John Larsen, Rhodium Group; and Jesse Jenkins, Princeton ZERO Lab. | Resources for the Future

It also links the permitting of solar and wind projects on federal land to corresponding sales of onshore and offshore oil and gas leases.

RFF estimates the new leases will generate about 20 million metric tons of GHG emissions by 2030, a figure that would be more than offset by the 4 billion-ton cut in emissions from the electric power sector, Rennert said.

Orvis detailed EI’s modeling assumptions ― that 2% of the millions of acres available for oil and gas leasing would actually be sold at auction, and emissions from any wells drilled would be spread out over time. EI’s conservative estimate of emissions from those wells came in at 50 million MT, Orvis said.

“And that means for every one-ton increase in emissions from the oil and gas lease provisions [in the IRA], there’s 24 tons of emissions reductions from all the other provisions in the bill,” he said.

EI’s estimate of GHG emission reductions is 37 to 41% below 2005 levels by 2030, he said. The bill would also create about 1.5 million full-time jobs by in the same time frame, which should increase the national gross domestic product by close to 1%, he said.

The IIJA Connection

John Larsen, who lead’s Rhodium Group’s energy system and climate policy research, acknowledges that IRA contains many provisions that would help households fully electrify their homes or use the bill’s other tax credits for much bigger energy savings than the firms’ more modest estimates.

Rhodium’s analysis represents “what happens on an aggregate basis from all provisions,” he said in an email to RTO Insider. But, in a separate research note, Larsen also says that the IRA reductions are just one part of other factors —”improving energy market conditions and technology deployment driven by current policy” that Rhodium anticipates will drive down home energy costs by $730 to $1,135 per year.

Similar to RFF, Rhodium’s analysis of the IRA includes scenarios based on oil and gas prices and associated emissions. Thus, higher oil and gas prices produce a lower estimate of emission reductions, while lower prices could drive higher emission reductions.

With three scenarios — low, middle and high emissions — Rhodium is projecting the IRA will cut emissions 31 to 42% by 2030 compared to a 24 to 35% base case using existing policies, including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Larsen expects that the IRA will provide added market momentum to IIJA’s funds for the development of emerging technologies like carbon capture and green hydrogen. (See What’s in the Inflation Reduction Act, Part 2.)

“The two bills are going to interact in a really important, powerful way,” he said.

“What the IIJA did was start that first level of deployment — demonstration projects, first commercial-scale [projects] — but there’s nothing after that to keep pulling that technology into the market. … We see the [difference] between a conventional hydrogen price and clean hydrogen getting closed in some instances because of the IRA tax credit provisions.”

Still, because of its “nascent nature,” Larsen does not expect green hydrogen to “contribute meaningfully to total GHG reductions through 2030; [the IRA] gets that technology to scale so it’s ready to go for the next wave,” he said.