The first time I heard an energy industry official mention the word “flexibility” was back in the early 2010s, when I was a fledgling energy reporter at The Desert Sun in Palm Springs, covering the permitting and construction of an 800-MW natural gas power plant to be located north of the city. The Sentinel plant and its eight, 90-foot-tall emission stacks were needed for system flexibility, a representative from CAISO told me.

As more and more variable renewables came online ─ like the hundreds of wind turbines also located north of Palm Springs and the first utility-scale solar projects on federal land east of the Coachella Valley ─ flexible power that could come online quickly was critical, the official told me. And back then, fast and flexible meant natural gas.

Sentinel was a peaker ─ ideally used only to fill gaps in power supply at times of high demand ─ and was licensed to operate only one-third of the time. It could fire up in about 10 minutes, and according to an environmental impact report that I read in detail, could put up to one million tons of carbon dioxide per year into the region’s already polluted air.

(Despite its status as a major resort area ─ and home to one of the country’s largest music festivals ─ the Coachella Valley has notoriously poor air quality, due in part to the hundreds of diesel-powered 18-wheelers rolling through it daily on the Interstate 10 highway.)

CAISO ran its first demonstration projects using energy storage for system flexibility between 2014 and 2016 ─ after I left Palm Springs ─ but the results were impressive. I was in D.C. at the Smart Electric Power Alliance by then and remember another conversation with a contact at CAISO, who told me the storage was faster and more flexible than a natural gas peaker.

Ten years on, California has 17 GW of energy storage online, allowing the state to ride out summer heat waves ─ just one sign that flexibility has gone from marginal to mainstream. It also is a core attribute of the various scenarios and solutions being discussed to meet the snowballing estimates of U.S. electric power demand that drove headlines in the industry and mainstream media in 2025.

2026 is going to be all about how to further integrate flexibility as part of a clean, reliable and affordable electric power system. The technology is available, with prices going down and advanced capabilities expanding at speed and scale, powered by artificial intelligence. The lag, as ever, is on the policy and regulatory side.

The questions will be about what kind of new or different market mechanisms and regulatory guidelines will be needed to ensure the U.S. power system can take full advantage of all the different value and revenue streams flexibility can offer.

Specifically, regulators have yet to figure out how to fully integrate and compensate distributed technologies, like storage, which do not fit into traditional categories of supply and demand ─ generation and load, charge and discharge ─ and how these different technologies are rated on the grid.

But the typically glacial pace of regulation ─ with endless pilot projects and decisions often years in the making ─ is no longer tenable. Demand growth, rising electric bills and the need for system reliability and resilience are converging to accelerate the pace of change, with big tech hyperscalers ─ companies like Google building gigawatt-scale data centers ─ pushing all the various envelopes involved.

What is ahead will be exciting, uncomfortable and unavoidable for all stakeholders, including President Donald Trump and his supporters, who, despite all evidence to the contrary, are stubbornly clinging to fossil fuels as the primary solution for all the challenges of demand growth.

The Flex Front 2025

Any discussion of grid flexibility probably should start with a working definition. In grossly oversimplified terms, we know that our electric power system is overbuilt to handle periods of high demand that may occur only a handful of times each year, which means it often is grossly underused. That excess capacity can be optimized with grid-enhancing technologies ─ like advanced conductors and dynamic line ratings ─ which in turn can allow for the flexible integration of different forms of carbon-free generation and storage.

Further, electric power can be “flexed” at all levels of the system, from residential, commercial and utility-scale to distribution and transmission.

That flexibility in and of itself framed new and innovative views of the grid in 2025, beginning with a Duke University study, released in February, suggesting that if data centers were willing to curtail their electric use even .25% of the time, it would open up space on the grid for 76 GW of new generation. A curtailment rate of 1% could mean enough headroom to add 126 GW of new power.

The study has been widely cited, and Tyler H. Norris, its lead author, quickly became a much-sought-after speaker at industry conferences and webinars. In November, Google hired Norris to lead its market innovation and advanced energy initiatives.

Other key developments on the flex front included:

-

- The July 29 virtual power plant demonstration in California: More than 100,000 residential batteries simultaneously discharged for two hours, from 7 to 9 p.m., pumping out 539 MW of electricity, or the equivalent of a mid-sized power plant. An analysis of the demonstration by The Brattle Group concluded that the aggregation of behind-the-meter solar and storage “can deliver reliable, utility-scale capacity at a significantly lower cost than traditional solutions.”

- Energy Secretary Chris Wright’s Oct. 23 directive to FERC: Wright proposed new rules for the interconnection of “large loads” ─ that is, data centers ─ which would allow expedited approvals for co-location of centers and generation if power at such facilities could be curtailed or dispatched by a grid operator. FERC received more than 200 comments on Wright’s proposed rules, with hyperscalers in particular opposing any rule that linked expedited interconnection to curtailment controlled by grid operators or utilities.

- The Electric Power Research Institute’s DCFlex initiative: Significantly, EPRI launched this new program less than a week after Wright’s directive to FERC, with the goal of developing data centers as flexible grid assets. A heavy-hitting list of project collaborators includes Google, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Schneider Electric, along with major utilities, RTOs and ISOs. An interactive map on the DCFlex website shows that utilities in 41 states already have some kind of flexible load or demand management programs.

Clearly, everyone ─ even Chris Wright ─ knows that change is coming; flexibility will be a critical must-have, and those who are not ready or willing to innovate and invest will be left behind.

Above Politics

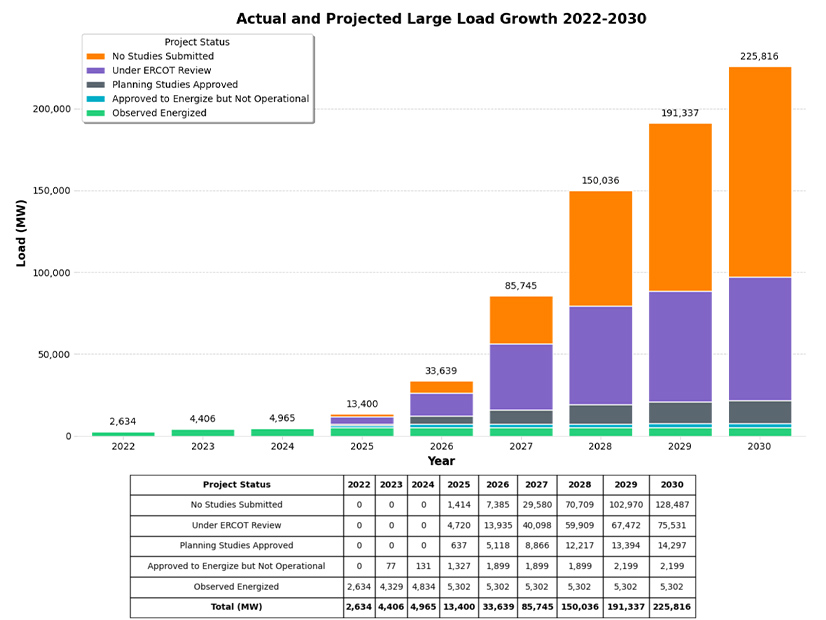

The physics, economics and politics of the next few years are well known. Estimates of the amount of new power the United States will need by 2030 increase with almost every new report. Back in February, the Duke University study estimated that data centers alone would drive 65 GW of new demand by 2029.

An ICF report from May called for 80 GW of new power to come online per year for the next 20 years, while in November, Grid Strategies upgraded an earlier estimate of 128 GW needed by 2030 to 166 GW.

The turbines that will power new natural gas plants could take years to deliver due to material and labor shortages and leave consumers vulnerable to the turbulence of natural gas prices. Renewables are cheaper and faster to build ─ and according to interconnection.fyi, still make up about 88% of projects sitting in interconnection queues nationwide ─ but face a virtual obstacle course as the Trump administration, RTOs and some utilities prioritize natural gas and nuclear.

Natural gas and renewables also will require new transmission and streamlined, accelerated permitting, all of which, including new data centers, are likely to face local opposition.

And electric bills are going nowhere but up ─ period. The ICF report estimates that residential rates could rise 15 to 40% by 2030, depending on the region.

Flexibility redefines everything and, again, is available immediately with existing technologies, which will get cheaper and smarter with speed and scale. This is why it will be essential for system evolution at all levels in 2026.

Flexibility turns grid-edge renewables from variable or intermittent to flexible and dispatchable resources that can shave peak demand, as seen in California’s VPP demonstration. Homes, businesses and data centers all can serve as flexible grid assets, which can help cut electric bills and drive behavioral change.

Consumers increasingly will see the value of adopting technologies that combine energy efficiency with flexibility ─ like solar and storage ─ so they can participate in even more sophisticated demand management programs.

In addition, upgrades that make existing transmission and distribution systems more flexible could allow for more distributed renewables, while triggering less local NIMBYism and reducing the need for new fossil-fueled generation.

In other words, flexibility is a no-brainer. It is above politics, and it just makes sense.

Fail and Scale Fast

President Trump notwithstanding, clean energy will continue to grow ─ though at a slower rate ─ in 2026 because it is faster, cheaper, cleaner and more flexible than fossil fuels. But the more significant paradigm shift this year will be toward policies, again at all levels, that promote the adoption of flexible technologies, ensure they are valued and compensated appropriately and accelerate permitting.

While Trump and some major players in the industry frame the current crunch in demand growth as an “energy emergency,” it actually is a long overdue and extremely cool opportunity for the electric power sector to reinvent itself. It has been dragging its feet on a 21st-century makeover, while its customers increasingly move at the blistering speed of AI.

High-tech hyperscalers are setting the pace. They want power, speed and flexibility for their data centers. They have the technology, the experts and the money to invest in system change; they know how to fail and scale fast; and they do not like waiting for regulators or utilities unless they absolutely must.

Interconnection policies have become the front line of change, where expedited approvals for projects turn on their ability and willingness to flex their power. Texas pioneered this kind of “conditional interconnection,” now codified via SB6, signed into law in June. California followed suit in August with its Limited Generation Profiles policy, which limits the amount of power distributed projects can export to the grid at times of system stress.

What is particularly exciting here is the implicit acceptance of flexibility as a central attribute of the grid and how that in and of itself redefines reliability and resilience.

PJM will provide the acid test of this approach as it works to comply with FERC’s recent order requiring an overhaul of the RTO’s interconnection policies for new generation co-located with data centers. In particular, the order requires PJM to adopt rules and the associated tariffs for co-located generation that can self-curtail or flex its demand on an interim or regular basis. (See FERC Directs PJM to Issue Rules for Co-locating Generation and Load.)

Any final rules from FERC promoting flexible interconnection should send a signal to other grid operators, states and utilities. Wright’s directive called for the federal regulators to complete work on his proposed rules by April, which would be warp speed for the commission, especially given the many concerns raised by stakeholders.

Demand management also is going to move fast. With Tyler Norris on board, we can expect to see new initiatives in this area from Google, which has signed flexible demand agreements with the Tennessee Valley Authority and Indiana Michigan Power. Meanwhile, Amazon is promoting grid-enhancing technologies as a way to get more renewables online.

Building on California’s demonstration, 2026 will see a ramp in VPPs. A recent article in Energy Storage News details three new VPPs being launched by a range of developers and utilities in California, as well as in Texas, Washington, Arizona and the Tennessee Valley. One example is a new partnership between software developer Leap and independent power producer Enel North America that aims to connect commercial distributed resources to utility demand management programs.

Why is any of this important? As flexibility becomes the new normal, it makes us think about electric power differently. It redefines our relationship to how we produce it, how we use it and what we can do with it. It makes us aware that we as consumers have an active role to play here, and that we can do more than complain about rising electric bills and then pay them.

Let us also remember that when we talk about flexibility and renewables, we are talking about climate change and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, whether we use the actual words. We have shifted from an environmental to a practical, business case for climate action, which is equally if not more effective.

Coming full circle, in 2024, the Sentinel plant was approved for a 17.18-MW, 34.36-MWh battery storage system to provide black start capability, so the plant can restart itself even if it goes offline.

When peakers need extra flexibility, we are way past the point of no return; 2026 is going to be a good year.