New all-electric buildings will likely save Massachusetts homeowners thousands because of increasing gas system maintenance costs and the effects of a shrinking gas rate base, according to a report released Feb. 8 by Groundwork Data.

The report said construction costs for all-electric residential buildings are now within 1% of buildings that rely on fossil fuels, while electric heating operating costs are lower than those for oil and propane but slightly higher than natural gas.

“All-electric new construction is poised to quickly become much more cost-effective than gas under expected emissions regulations and increasing average gas delivery costs,” the report said.

The analysis was commissioned by ZeroCarbonMA, a climate advocacy group that has pushed to ban fossil fuels in new buildings in the state.

The report estimated that the state will hit an inflection point around 2030, when electrified heating customers will start to see cost savings relative to gas customers, with the savings steadily increasing in the coming decades, reaching $4,000 annually around 2055.

“The three key drivers behind this inflection in energy costs are the increasing cost of gas pipeline maintenance (largely to manage leak-prone pipe), the declining consumption expected with even modest levels of heating electrification and potential efforts to regulate emissions,” the report said.

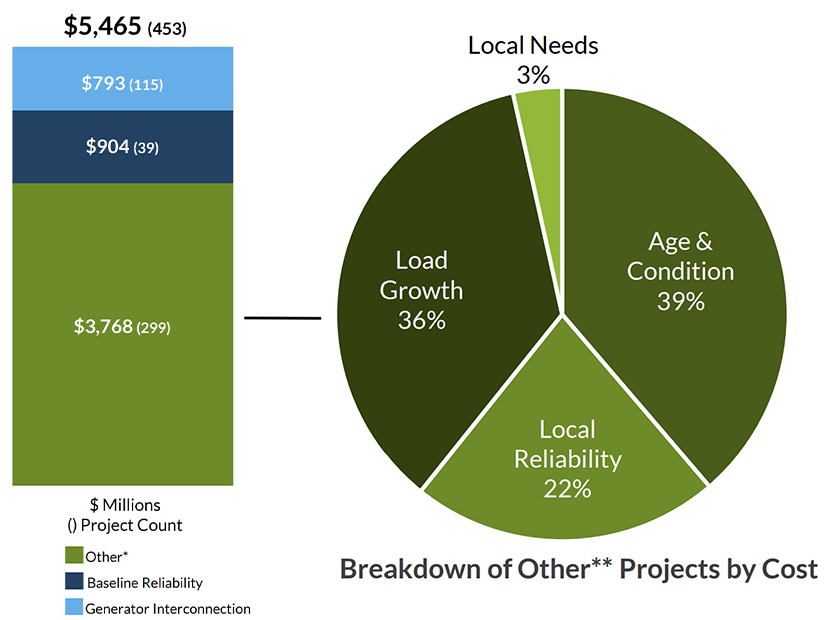

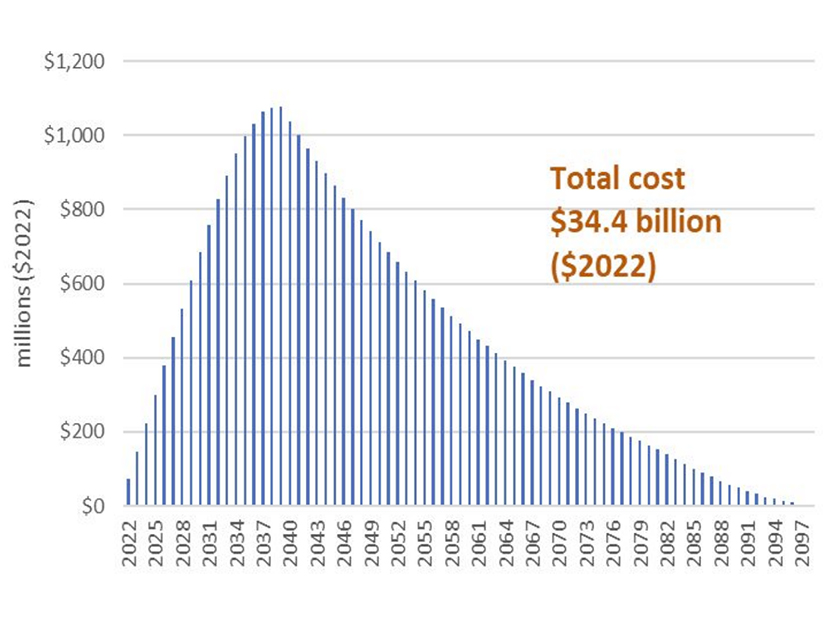

While building electrification is likely to shrink the gas rate base, maintenance costs are projected to accelerate because of the state’s Gas System Enhancement Program (GSEP), which encourages gas utilities to replace leak-prone pipes to reduce methane emissions.

In an analysis presented to the state in 2023, Groundwork estimated that GSEP investments between 2022 and 2039 will cost ratepayers more than $34 billion, with costs peaking around 2040. (See Mass. Gas Working Group Finalizes Recommendations to Legislature.)

Increasing gas rates will likely be most burdensome for low- to moderate-income ratepayers who have less ability to switch to electric heating when gas rates accelerate, the report noted. Because a portion of the costs associated with new hookups is spread throughout the rate base, new gas connections could exacerbate affordability issues for existing customers.

Groundwork’s Mike Walsh, the author of the report, said there is limited public data about how much of the cost of new gas hookups is covered by the general rate base. The formulas utilities use to determine the breakdown of costs between new customers and the rate base assume that these costs will eventually be recovered from customers over the extended life of their gas connection, he said.

Walsh noted that the researchers did find data from one of the state’s smaller utilities that indicated that the rate base was on the hook for about 80% of the cost of a pipeline extension to connect a new customer.

“Most of these homes that are being built in new construction, whether it’s commercial or residential, are for more affluent customers,” Walsh said. He added that if the new customers leave the system before the full costs can be recovered, “that’s an equity concern. We don’t know if that’s happening here because we don’t know what those formulas are.”

For customers looking to electrify and exit the gas system, retrofitting existing buildings is not cheap. Electrification retrofits could cost $16,000 to $17,000, which could be avoided entirely if the building was built all-electric in the first place, the report said.

“The state is going to be on the hook for more and more retrofits,” said Lisa Cunningham of ZeroCarbonMA. “We’re going to have to spend even more money retrofitting the gas infrastructure that’s going in today.”

Cunningham emphasized that as gas costs accelerate, the costs of maintaining the system could increasingly fall on ratepayers who can’t afford the expensive retrofits needed to exit.

The scope of retrofits looming over the state is significant. The final 2021 report from the state’s Commission on Clean Heat estimated that the state will need to electrify 500,000 residential homes by 2030 and 1.3 million homes between 2030 and 2050.

Over the past few years, the state has passed several laws encouraging fossil fuel-free buildings. In 2021, the legislature created a municipal opt-in specialized energy code that incentivizes the construction of all-electric buildings, and in 2022 it created a pilot program to allow 10 municipalities to ban fossil fuels in most new buildings.

However, all-electric buildings are far from a mandate for most of the state, and gas utilities have continued to add new connections in recent years. In the current legislative session, top lawmakers have been hesitant to expand the 10-town pilot program to include additional municipalities, citing the need to evaluate the data from the pilot.

At the Feb. 7 deadline for the joint committees to report on bills, the legislature’s Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy (TUE) Committee declined to favorably report several bills to expand the pilot.

The Senate side of the committee did favorably report several bills targeting the gas system, including S.2105, aimed at promoting and facilitating the transition to clean heating technologies, and S.2135, which would establish a moratorium on new or expanded fossil fuel infrastructure in the state. (See Mass. Lawmakers Aiming for an Omnibus Climate Bill in 2024.)

The recommended bills from the House side do not include much to “move the needle on building emissions. … It’s more in the Senate,” Larry Chretien, of the Green Energy Consumers Alliance, told NetZero Insider. “Things like the report coming out of ZeroCarbonMA, I hope, will inform that discussion.”