BOSTON — Massachusetts lawmakers and climate advocates held a legislative briefing Wednesday on a set of bills looking to spur the decarbonization of the state’s heating sector.

The overarching goal of the legislation is to redirect investment away from natural gas infrastructure and toward clean energy technology like heat pumps and networked geothermal.

“We need to stop powering our homes and household appliances with gas,” said Senate Majority Leader Cindy Creem, who also serves as the chair of the Senate Committee on Global Warming and Climate Change. “It’s simply not compatible with our climate ambitions, and it’s not good for our health.”

Massachusetts is lagging behind its 2050 net-zero goal for its buildings sector. While the number of electric heat pump installations in the state has rapidly increased — from about 500 in 2020 to about 18,000 in 2022, according to the Boston Globe — a 2020 report commissioned by the state found that the commonwealth needs to electrify about 100,000 homes each year for the next 25 to 30 years to meet its climate goals.

Aiming to address this issue and spur the transition to electrified heating systems, Senate Bill 2105 and House Bill 3203 (An Act Relative to the Future of Clean Heat in the Commonwealth), contain a wide range of provisions that would transform the role of gas utilities in the state and incentivize non-emitting clean heat technologies.

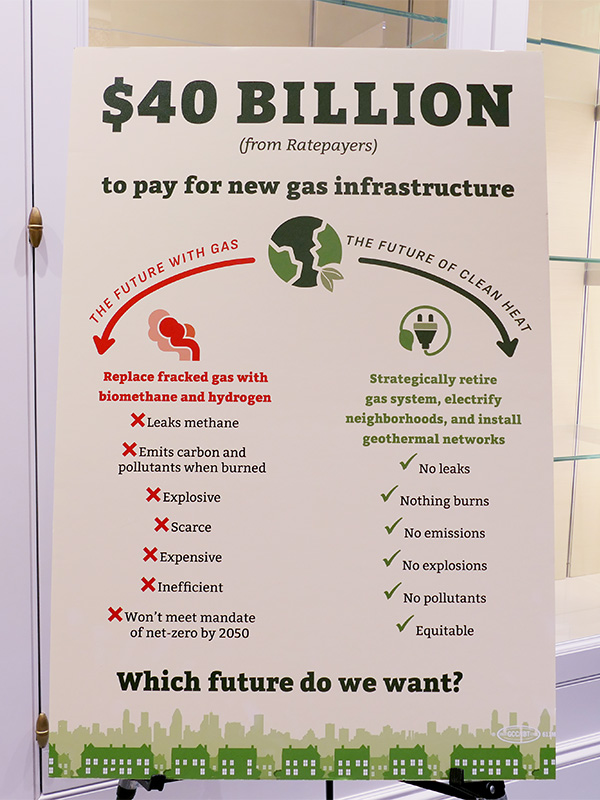

Infographic promoting the bills | © RTO Insider LLC

Infographic promoting the bills | © RTO Insider LLC

The bill would authorize the state’s gas utilities to replace gas pipes with electric heat pumps and networked geothermal systems, and allow gas companies to sell electrified home appliances. While National Grid (NYSE:NGG) and Eversource Energy (NYSE:ES) are currently collaborating with the Home Energy Efficiency Team (HEET), a clean energy nonprofit, on networked geothermal pilot projects in the towns of Lowell and Framingham, they currently are limited in their ability to expand their programs to meet demand outside of the pilot projects.

The legislation would also create a “thermal transition trust fund” within the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center (MassCEC) to provide funds for residents to replace gas appliances with electrified alternatives, with priority given to low- and moderate-income residents. It would also provide funding to utilities to train and retain workers in the transition away from gas. The fund would be paid for in part by gas customers at a cost of 1.5 cents/therm, which advocates estimate would total about $20 million annually, about half of the total.

The bill would also require gas utilities to provide the state’s Department of Public Utilities (DPU) with detailed plans to transition entirely off emitting energy sources by 2050, while also retaining gas workers, by the end of 2025.

Advocates also addressed the plans presented by gas utilities in the DPU’s 20-80 proceedings, which would decarbonize the gas system using “fossil-free fuels” like green hydrogen and biomethane. Climate groups have pushed back on these plans, arguing that these alternative fuels are scarce, expensive, hazardous and ultimately still damaging to the climate.

The gas utilities “have submitted plans that claim to decarbonize the system, but the reality is that it’s just business as usual,” said Rep. Steven Owens, one of the bill’s cosponsors in the House of Representatives.

The act would prohibit the use of hydrogen gas for heating buildings and limit the use of biomethane to gas with net-zero lifecycle emissions.

Advocates made the case that strategically shifting investments away from replacing gas pipes, which could quickly become stranded assets, and into clean heat technologies would also benefit ratepayers, who are facing a multibillion-dollar bill for the state’s Gas System Enhancement Program (GSEP). Estimates of GSEP’s total costs range from $13.4 billion to about $40 billion.

Making up for Bad Math

In Massachusetts and across the country, climate advocates have long made the case that greenhouse gas inventories based on EPA accounting methods dramatically undercount the scale and impact of methane emissions, which are responsible for about 30% of climate warming.

“The problem that we’re solving is even bigger than it appears today because we are using outdated science,” said Zeyneb Magavi, co-founder of HEET.

To update the state’s accounting methods, the Making Methane Accounting Truthful Helps (MATH) Act (Senate Bill 2092 and House Bill 873) would require the state to calculate the warming impact of its methane emissions on a 20-year timescale, along with the 100-year time frame currently used. Methane is a short-lived gas in the atmosphere, and the magnitude of its warming impact depends on the timescale used to calculate it. Over a 20-year period, the global warming potential (GWP) of methane is about three times larger than its GWP on a 100-year basis.

The state’s inventory would need to account for all gas leaked in the process of transmission, storage, distribution and end use. The bill would also require a review of accounting methods every three years, looking at the best available science.

However, as the bill is currently written, it does not target the full scope of issues in the state inventory identified by experts and climate advocates. The legislation does not address the state’s chronic underestimation of methane leak rates from the gas system: A 2021 study by Harvard University researchers found methane emissions from the gas system in the greater-Boston area to be about six times higher than the estimates from the state’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

The bill also would not address how the state calculates lifecycle emissions from biofuels like biomethane, which the state essentially considers to be net-zero but are typically associated with some level of climate impact, though the impact can vary significantly based on the fuel’s source. The bill also doesn’t contain language considering out-of-state emissions associated with gas consumed in Massachusetts.

Advocates said that they hoped to address these issues in future legislation.

Democratizing the DPU

The presenters also spoke about the importance of updating the intervener process at the DPU. House Bill 3137 would require the DPU to allow municipalities, groups of ratepayers and nonprofits with utility law expertise to intervene in department proceedings.

“The DPU’s intervenor process is in desperate need for democratization,” said Rep. Jennifer Armini, the bill’s sponsor. “If we’re going to have safe, clean communities, and fight climate change, we need to change the processes that are preventing progress.”

The legislation would also require utilities to provide information to ratepayers and municipal officials about pipeline characteristics and risks, and return streets to good condition after conducting pipeline work.

“Municipalities just don’t have enough information about the gas system, and we have no authority to require that information,” said Lise Olney, chair of the Wellesley Select Board.

Next Steps

Advocates called on state legislators to sign on as co-sponsors of the three bills, which will all face scrutiny in the state’s powerful Joint Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy Committee.

A similar bill to the “Future of Clean Heat” failed in the previous legislative session. National Grid, the state’s largest gas utility, lobbied against the bill, while Eversource, Unitil and Berkshire Gas (a subsidiary of Avangrid) registered their lobbying on the bill as “neutral,” as they did for nearly all other bills.

National Grid did not respond to requests for comment. An Eversource representative wrote that the company was still reviewing the bills but noted that it will “continue to explore an array of solutions to responsibly decarbonize our natural gas system, while still providing safe and reliable heating service to all of our customers at the lowest cost possible.”