Ask 10 experts whether RTO markets and electricity deregulation lead to lower prices and you are liable to get 10 different answers.

Debates around the benefits of restructuring have been going on since the states started unbundling monopoly utilities a quarter century ago. A new skirmish arose on #energytwitter earlier this month in response to a New York Times article provocatively headlined “Why Are Energy Prices So High? Some Experts Blame Deregulation.”

Citing an analysis of Energy Information Administration data by energy researcher Robert McCullough, the article says “California and the 34 other states that have deregulated all or parts of their electricity system tend to have higher rates than the rest of the country.” (See sidebar, A ‘Deregulation’ Debate by the Numbers.)

Rorschach Test

RTO Insider reached out to a range of sources to get their thoughts on whether deregulation and organized wholesale markets have benefited customers.

Competition “is a Rorschach test,” energy consultant Alison Silverstein told RTO Insider. “And you can manipulate numbers, particularly electric rates, to say anything you want to.”

Former FERC Chair Pat Wood III | © RTO Insider LLC

Former FERC Chair Pat Wood III | © RTO Insider LLCSilverstein’s old boss Pat Wood — who took over as chairman of FERC during the California Energy Crisis and chaired the Texas Public Utility Commission when that state started its journey to a fully deregulated, or restructured, wholesale and retail power market — is firmly in the pro-market camp.

“Competition on its worst day is better than I ever could be as a regulator on my best day,” said Wood, who is now CEO of energy storage developer Hunt Energy Network.

Rate regulation is intended to ensure utilities with monopoly territories earn enough to attract investment while keeping prices affordable. No matter how talented regulators are, Wood said, “there’s no way you can really substitute for the efficiencies and discipline of a market on pricing for customers.”

RTOs were created to lower costs to end-use consumers but have failed to do so, said Public Citizen’s Energy Program Director Tyson Slocum. The states that did restructure started with higher prices to begin with for a variety of reasons.

“But those prices remain just as high or higher today than they did 20 years ago, compared to other states,” Slocum said. “So, what’s clear is that RTOs are failing to deliver the promise of lower prices and that should be of great concern to FERC. If the entire purposes for doing something isn’t happening, then you should probably investigate as to why.”

Severin Borenstein, U.C. Berkeley | U.C. Berkeley

Severin Borenstein, U.C. Berkeley | U.C. BerkeleyPlenty of others are somewhere in the middle with Severin Borenstein, a professor at the University of California Berkeley’s Haas School of Business and a member of CAISO’s board, whose work has found that it depends on other factors entirely.

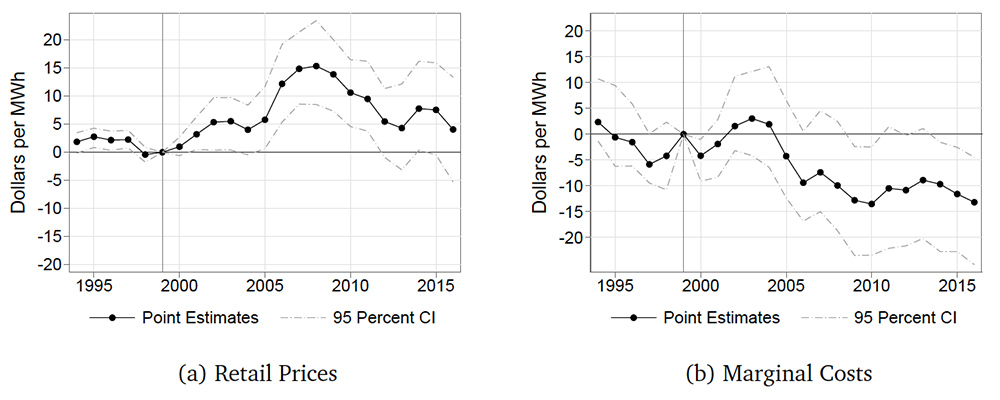

“The reality is that if you procure power through a deregulated wholesale market, the marginal supply sets the price,” Borenstein said in an interview. “Now, if gas prices are really low, you end up getting much better prices in a [competitive] wholesale market than you do in a regulated market.”

Natural gas is the most common marginal fuel in ISO/RTO markets around the country, which means that generators burning it most often set the locational marginal price (LMP) for other generators. If gas prices are high, then the vertically integrated states have cheaper prices because their generation is not paid a single price, Borenstein said.

Tyson Slocom, Public Citizen | © RTO Insider LLC

Tyson Slocom, Public Citizen | © RTO Insider LLCThe issue of whether RTOs lead to consumer savings was a hot topic before the shale revolution, when gas prices were trading at $7-8/MMBtu some 15 years ago.

“PJM was in absolute crisis,” said Public Citizen’s Slocum. “There was serious consideration of whether or not it had all failed because gas, which was setting the marginal cost, was punishingly high.”

The RTO model got “bailed out” by cheap natural gas from fracking, said Slocum. But now the markets are under strain again as gas prices were higher last year on average than any year since 2008, according to EIA.

Slocum and others also argue that the markets are under strain as renewables are growing, but many who spoke with RTO Insider argued that RTOs and their abilities to efficiently dispatch generation across a wide footprint are going to be key to making that transition happen affordably and reliably.

Economies of Scale

“I think ISOs have led to huge reductions in cost,” FTI Consulting’s Scott Harvey said in an interview. “Particularly in MISO, SPP and the Western EIM, where there was no power pool before. Having the coordinated dispatch of the ISO allows the region to use all of the transfer capability of the transmission system.”

Scott Harvey, FTI Consulting | © RTO Insider LLC

Scott Harvey, FTI Consulting | © RTO Insider LLCUnder the old rules, the available transfer capability used was a fraction of the total available — not because the people running the old utility balancing authorities were trying to keep the resource themselves, but because they had very limited views of where power was flowing, Harvey said. They had to make worst case assumptions because once the power started flowing, they had very limited abilities to change it even if they need to for reliability.

ISO-NE, NYISO and parts of PJM were already in tight power pools before their ISOs developed, but Harvey said PJM’s expansion has led to major improvements.

“If you think back to the polar vortex of 2014, PJM actually got through it without any load shedding,” Harvey said. “I doubt they could have if it was the old world with a bunch of fractionated utilities in the Midwest and Ohio.”

The benefits of stitched together balancing authorities came up again in the recent cold snap over the Christmas holiday when PJM was again stressed but did not shed load while individual utilities in the Southeast did, Harvey said. (See PJM Gas Generator Failures Eyed in Elliott Storm Review.)

Former FERC commissioner and North Dakota regulator Tony Clark, who is now a senior adviser at Wilkinson Barker Knauer, agreed that a clear benefit of RTOs is that they drive scale, which is hugely important in the electric industry.

Time for a Change in the Pricing Model?

The other common feature that is often credited with driving savings is security constrained economic dispatch, but Clark has doubts about the benefits of the ISO/RTO pricing model.

Former FERC Commissioner Tony Clark | © RTO Insider LLC

Former FERC Commissioner Tony Clark | © RTO Insider LLC“LMP pricing was designed around a system where most resources had very similar attributes,” Clark said. “They weren’t exact, but more resources were basically dispatchable, they were basically on demand. They might have longer, or shorter lead times, ramp times, things like that. But they tended to be dispatchable, and they tended to have a fuel cost, which is to say they have marginal costs.”

Weather-dependent renewables are not dispatchable, and they have free fuel so they have no marginal costs. But under the current structure they get paid whatever the most expensive plant needed is paid, which tends to be a natural gas unit.

“Under that scenario, do consumers still benefit?” Clark said. “Or would they benefit from some sort of average cost pricing? It’s a really interesting question.”

The idea of average pricing in wholesale power markets, and any other commodity market, is based on a misunderstanding of how bidding works, said U.C. Berkeley’s Borenstein.

“They wouldn’t bid lower if they knew they were going to be paid their bid,” he said. “They’d try to bid whatever the market clearing price is. The idea that everybody gets paid a uniform price is how commodity markets work, not just for electricity — for natural gas, for gold, for oats, for everything. There’s a market price, and people will get paid that market price because they’re selling a homogeneous good.”

ISO/RTOs Share Some Things in Common, But Have Many Differences

While RTOs have some common characteristics, they also have marked differences. ERCOT also helps administer a fully deregulated wholesale power market, while ISO-NE, NYISO and PJM are dominated by states that have also opened their retail markets, though none have gone as far as Texas.

MISO and SPP are largely dominated by traditionally regulated utilities, while CAISO is somewhere in between with community choice aggregation and capped retail competition for large commercial, industrial and institutional customers.

Beyond those regulatory issues, the markets have very different resources, and that can muddle the studies claiming to find savings or increased costs from ISO/RTOs, said NRG Energy Vice President of Regulatory Affairs Travis Kavulla.

“It wouldn’t matter whether New England was open to competition, or economically regulated at the moment; the fact of the matter is under either of those models it would be substantially exposed to the wholesale gas market,” Kavulla said. “New England happens to be a place where policymakers have decided not to build a lot of gas pipelines to domestic sources of gas, and so they have effectively exposed themselves to the European gas market, the global natural gas LNG market.”

Studies will take those effects and impute them to competition, when it really has more to do with the policies of the New England states, Kavulla said. California is another odd duck to squeeze into studies, he said.

“I don’t think any reasonable person would look at the amount of regulation and the amount of government policy related to the energy sector in California and conclude that it’s quote, unquote deregulated,” he added.

Retail Deregulation

Experts who spoke with RTO Insider were split on the benefits of full “deregulation” — where states have also opened their retail power markets.

Wood, who helped design the ERCOT market, still supports retail competition. The wide-open retail market in most of ERCOT is able to flow through the savings from wholesale competition to end-use customers. But in other states where utilities are still providing default retail service to customers it can be more of a muddle.

Ralph Cavanagh, Natural Resources Defense Council | © RTO Insider LLC

Ralph Cavanagh, Natural Resources Defense Council | © RTO Insider LLC“I’ve definitely been on the record for 20 years or so about making sure these default providers don’t suffocate retail competition,” Wood said. “So, you either stick with wholesale competition only and you have a very clear way of passing those benefits of low-cost generation, or lower cost generation, being passed through … or you have robust retail competition, like we have here, where retailers compete with the other ones to get your business, and so, they have to pass through those [lower] costs through.”

In between those two worlds, some middleman is likely to keep a share of any of the purported benefits of competition, he added.

The Natural Resources Defense Council’s Ralph Cavanagh was against the idea of retail competition when California was considering deregulating in the late 90s, and he recalls a debate with an executive at Enron on the issue.

“I asked the question publicly: What is in this for my mother?” Cavanagh told us. “To which his response was, ‘for the first time in history, your mother is going to be able to hedge her fuel price risks in the marketplace.’ Mercifully, people laughed at that.”

Cavanagh said small customers generally do not want to spend the time to learn about fuel price risks, though large commercial, industrial and institutional customers can benefit from such options.

“It is worth recalling that even large, sophisticated customers got swamped by the collapse of the California retail markets in 2000 and 2001,” he added.

Coordination Can Help Green the Grid

But when it comes to wholesale competition, Wood and Cavanagh are on the same page. The elimination of utility monopolies over generation has been going on since the 1970s, and no one is seriously considering reversing that, said Cavanagh.

The West outside of California is one of the two main areas, along with the Southeast, that lack an organized market. But in the former that is changing, and Cavanagh said it must do so to reliably transition the grid to a cleaner future. The West would not have made it through the massive heatwave this past September without major cooperation, where Arizona helped California and California helped Idaho maintain reliability.

“It became obvious to everyone that nobody cared what the political color of the state was,” Cavanagh said. “There’s a common interest to a fully functioning regional grid to which we are all connected.”

The CAISO-run Western Energy Imbalance Market has already expanded to cover most of the Western Interconnection, and it has saved billions of dollars so far.

“The most important thing we have to do now is to get the California legislature to open a path to fully independent governance for the California ISO,” Cavanagh said.

CAISO covers roughly one quarter of the generation and demand for power in the Western grid. Cavanagh said it was the best positioned entity to run the entire interconnection. SPP, however, is also fighting for a role in the Western Interconnection. (See SPP Makes Moves Out of the Southwest.)

The New York Times article that started a fresh round in this old debate spent a lot of time focusing on ballooning transmission and distribution bills that have little to do with markets.

Among the causes the Times cited for the higher prices in “deregulated” states are transmission and distribution costs and power company profits. “Deregulated states may spend more on transmission,” R Street Institute energy adviser Josiah Neeley acknowledged in a rebuttal published in Reason. “But that part of the market is still heavily regulated.”

Of the three big categories that feed into customers’ bills — transmission, distribution and generation — transmission is the smallest of the three. By opening up new resources to serve load, it puts downward pressure on prices, said Cavanagh.

“The entire country is now linked by high voltage interstate transmission, which is regulated on the provision of non-discriminatory access,” he added. “That’s the American model. We’re not divided on that; we’re divided on lots of other things, but not that.”

Transmission and distribution spending will need to increase to ensure the industry can reliably and affordably transition to the kind of cleaner grid needed to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

“The impact of broader transmission is to create lower wholesale power prices, which is the whole point,” Wood said. “You want to have broader markets to get access to the most cost-effective power, which is a bigger percentage of the customer’s bill than the wires charges are.”

Texas saw the benefits of expanding transmission with its Competitive Renewable Energy Zone lines, which were planned 15 years ago and came with a $7 billion price tag to bring wind from the resource-rich areas of the state to its cities. They wound up producing benefits that were five times their cost, Wood said.

The distribution system is going to need investment as well, to ensure that it can handle all the new sources of demand, such as plug-in vehicles and heat pumps, as well the growing distributed resources such as solar panels and batteries, he added.

Do Markets Help with Greening the Grid?

Silverstein argued that beyond transmission, wholesale competition has helped to weed out old, inefficient coal plants and replaced them with cleaner, more efficient natural gas — and in more recent years, renewable power.

Alison Silverstein, Silverstein Consulting | © RTO Insider LLC

Alison Silverstein, Silverstein Consulting | © RTO Insider LLC“God forbid, thinking about what we might have had for the rate of climate change and extreme weather if we hadn’t been enabling competition to shut out older and natural gas plants that were emitting even more carbon and were highly inefficient,” she said.

While most experts support the idea that transmitting renewables around a large, centrally managed grid helps, some questioned whether the competitive markets were really helping renewables. Public Citizen’s Slocum argued that the shift to renewables has put the system under strain, as seen with efforts from FERC under the Trump administration to block their impact on the market through the minimum offer price rule.

“Renewables are coming into the system in spite of the market design,” Slocum said. “They’re coming into the system because of regulatory mandates and financial incentives, which are not the markets. And as a result, it’s upending the market-based pricing system.”