Before it closed in 2015, the Hobet coal mine in southern West Virginia was one of the largest surface coal mines in the U.S. Now, Kansas City-based renewable developer Savion is planning to turn 3,000 acres of the site into the state’s largest solar farm with up to 250 MW, enough to power more than 30,000 homes.

The SunPark Solar project is one of many former coal mines being transformed into solar generating sites.

The Environmental Protection Agency recently identified 17,756 mine sites totaling 1.5 million acres, enough space to generate almost 90 GW of power. In June, the Department of Energy announced it would spend $500 million from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to transform former mine lands into “clean energy” sites. At least two of the projects must be solar; also eligible are geothermal, fossil fuel generation with carbon capture, energy storage and advanced nuclear. (See DOE Launches $500M Project to Put Clean Energy on Mine Lands.)

Founded in 2019, Savion was acquired in December by Shell New Energies (NYSE:SHEL) and has solar and storage projects in various phases across 31 states. The SunPark project is the result of an agreement the company reached earlier this year with SEVA WV, a West Virginia-based company that also hopes to develop an industrial park, lodging and recreation on the remaining 1,500 acres of the former mine.

The electricity Savion generates will be sold into the wholesale electric market. Commercial operations could begin between 2025 and 2028.

Elsewhere in West Virginia, a state formerly famed for its coal mines, FirstEnergy subsidiary Mon Power (NYSE:FE) is planning a solar power facility at a 44-acre reclaimed strip mine in Tucker County. That site is one of five locations where Mon Power plans to build a solar energy facility, for a total of 50 MW of renewable power generation. In May, Mon Power and FirstEnergy’s other West Virginia subsidiary, Potomac Edison, announced they had begun accepting West Virginia customer subscriptions to purchase power from the facilities through solar renewable energy credits (SRECs). More than 87,000 SRECs per year will be available when all five projects are up and running.

“We expect to obtain customer commitments this year for 85% of the solar renewable energy credits to be generated by the projects and will then seek final approval from the [West Virginia Public Service] Commission,” Will Boye, a spokesperson for FirstEnergy, said in an email. The company hopes to start full-scale construction next year at its first site, Fort Martin Power Station, with construction at the other four sites commencing in 2024 and 2025.

Silver Spring, Maryland-based Competitive Power Ventures (CPV) has two such projects in its portfolio: the Backbone Project in the western Panhandle area of Maryland, and Maple Hill Solar Farm in Cambria County, Pennsylvania. The former will generate 175 MW, enough to power roughly 30,000 homes. That project is waiting for an interconnection agreement with PJM, CPV’s Matt Litchfield said in an interview. “We hope to start construction in the next six months.” The Pennsylvania project will generate 100 MW, after an investment of more than $200 million, he said.

Seven Sites on Nature Conservancy-Managed Lands

The Nature Conservancy announced in July 2021 that it had reached agreements with Sun Tribe, based in Charlottesville, Virginia, and Washington, D.C.-based Sol Systems, which will build solar energy facilities on former coal mining lands that the environmental group manages in southwestern Virginia.

In September 2021, Dominion Energy Virginia (NYSE:D) announced its own partnership with the Conservancy for the Highlands Solar project, which will reuse about 1,200 acres of the former Red Onion surface mine and surrounding properties in Wise and Dickenson Counties. The partners said the project will generate approximately 50 MW. Additional benefits for the area could include “an increase in local tax revenues, the ability to provide additional funding through solar siting agreements, and the creation of clean energy jobs,” they added.

Dominion plans to begin construction in 2024 or 2025, subject to approval by the Virginia State Corporation Commission, and will use the project to work toward its mandate under the Virginia Clean Economy Act to produce its electricity from 100% carbon-free sources by 2045.

While most of the Cumberland Forest Project that the Nature Conservancy manages — almost 253,000 acres in southwestern Virginia, eastern Tennessee, and eastern Kentucky — consists of woodlands, it includes seven former coal mining sites as well, including the Highlands Solar site, five other sites in Virginia, and one just over the state line in Tennessee. Sun Tribe is developing the latter six sites, Brad Kreps, Clinch Valley Program Director for the Nature Conservancy, said in an interview.

The Conservancy says the three companies’ solar farms will cover nearly 1,700 acres and generate an estimated 120 MW.

“We are trying to find ways to create benefits for nature and new economic benefits for localities, such as tax revenues and jobs,” Kreps said.

But he conceded that most of the job creation involved will take place during the construction phase of the projects; no one expects the new solar farms to replace the number of jobs lost with the demise of mining. “It doesn’t take very many people to operate the facilities,” he said.

According to job posting site Indeed, solar panel installers in Virginia average about $24.50 per hour. Less than 12% of construction workers in the solar industry are unionized, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association. Although that is less than the national average for construction, it is double the 5.6% union participation rate reported in 2020 for the mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction segment, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

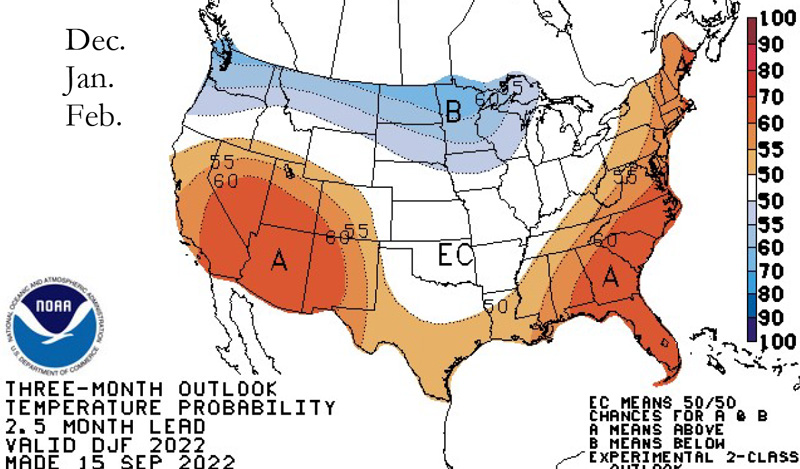

But while converting coal mine sites to solar won’t provide all the economic benefits that have been lost in Appalachia, supporters say it is essential to use sites such as these to minimize the need to convert farmland and woodlands. Princeton University energy and climate expert Jesse Jenkins has estimated that the most cost-effective scenario for reaching net-zero emissions will require solar over an area equivalent to the states of Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts.