Doubts continue to swirl around which version of MISO’s future fleet mix is appropriate for long-range transmission planning: the RTO’s or the Independent Market Monitor’s.

MISO pledged additional examinations of its fleet prediction during a stakeholder teleconference Monday, but that did little to quell reservations on either side of the debate.

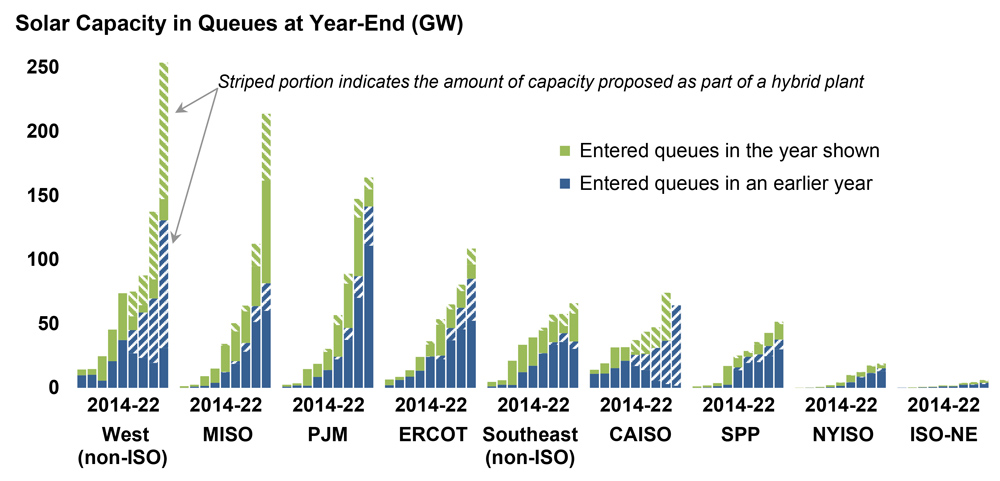

Monitor David Patton said he continues to have misgivings about MISO’s 20-year fleet assumption that’s dominated by nearly 250 GW in anticipated wind and solar additions alongside 53 GW in gas and other flexible generation and 31 GW of standalone battery storage.

MISO is using that fleet assumption to plan the second portfolio of its continuing long-range transmission plan (LRTP). The RTO says recent studies are showing its estimate of the future fleet holds up well and should be used in the multibillion-dollar portfolio.

Now that it has had time to conduct several tests, MISO says it has determined that its middle-of-the-road, 20-year planning future, referred to as Future 2A, “is most aligned with an optimized, least-cost expansion that meets member goals.” Director of Economic and Policy Planning Christina Drake said MISO continues to strive to “make sure we have a least-regrets portfolio.”

Patton, however, countered, “We continue to believe Future 2A is just not a reasonable basis for planning.”

Future 2A underwent an update last year to include members’ more aggressive decarbonization goals. Senior Director of Transmission Planning Laura Rauch said MISO will conduct more sensitivities for 2A based on different variables. The RTO is planning a new sensitivity based around hypothetically reduced incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act to see if its projected resource expansion changes meaningfully.

“We’ll continue to look for answers, but quite frankly, the answers that we get might not be the ones you’re looking for,” MISO Vice President of System Planning Aubrey Johnson told stakeholders.

MISO planners are prepared for contentious LRTP workshops, he said. “There’s a lot at risk. There’s a lot at stake. And we don’t take these meetings lightly.”

Drake said there have been many questions over how MISO arrived at its future fleet assumptions. She said MISO’s envisioned resource mix is “rooted in the reality of member plans” and that the LRTP is developed to optimize the delivery of members’ decarbonized future fleet. She also said MISO developed the second future over 18 months of stakeholder engagement.

Customized Energy Solutions’ David Sapper said numerous stakeholder meetings are not a “proxy” for the actual vetting of the future resource mix used for planning.

MISO: Monitor’s Fleet Vision More Expensive

MISO said it tested both the Monitor’s ask that it study more natural gas and battery storage resources and a scenario in which capacity accreditation is drastically reduced. It said both comparisons showed that its own version of the future resource mix under 2A represents a “least-cost expansion while considering state and member goals and resource economics.”

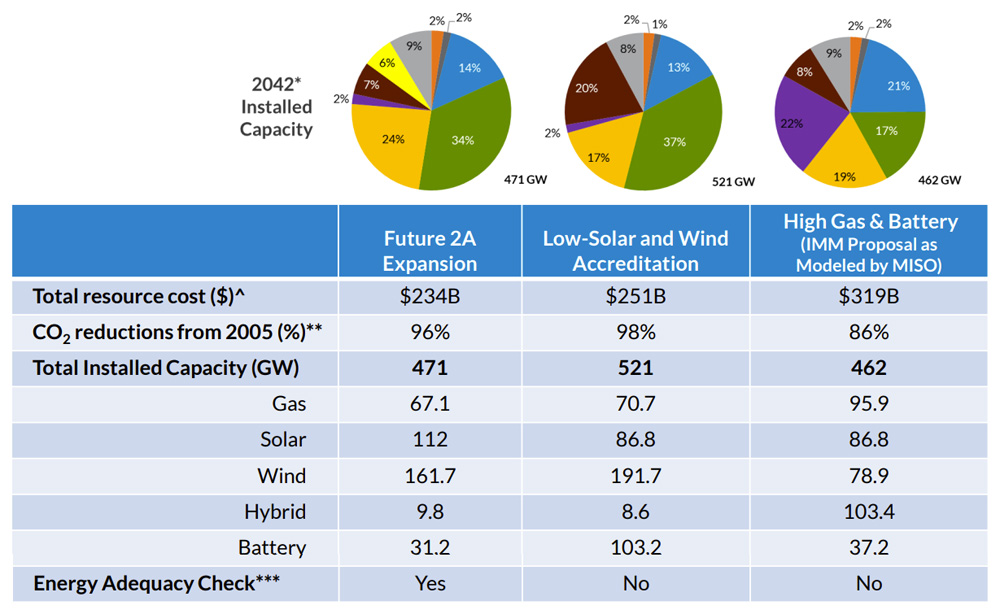

The RTO found wildly different fleet predictions between its version, the Monitor’s and the low accreditation future. It expects the total installed capacity under 2A to reach 471 GW by 2042 and cost $234 billion. It said if it introduced more gas resources and battery storage in place of renewable generation — as the Monitor recommended — costs would climb to $319 billion for 462 GW of capacity in the same time frame.

According to MISO, the Monitor’s version of the resource mix would include 103 GW of hybrid renewable and storage resources and nearly 96 GW in gas generation, with 83 GW less in wind resources and over 25 GW less in solar generation from the RTO’s prediction. Future 2A calls for 67 GW in natural gas and just 10 GW worth of hybrid resources.

In the reduced capacity accreditation scenario, MISO found a $251 billion resource expansion for 521 GW in installed capacity. That scenario returned a drastic spike in standalone battery storage to 103 GW by 2042.

But Patton said the amounts MISO inferred from his recommendations are faulty.

“The math is obviously wrong. … Your costs are obviously wrong,” Patton told MISO planners. “I don’t want anyone coming away from this thinking this is correct.”

Patton offered to consult with MISO on a joint hypothetical case of his version. He said there’s “no way” his would necessitate more than 100 GW of hybrid resources.

Drake said MISO “triple checked” its cost and capacity conclusions under the Monitor’s fleet predictions with more gas and battery resources. Rauch said MISO worked with the best information from the Monitor and said she was “frustrated” that it disagreed with the RTO’s outcome.

“We’re looking at roughly a 9-GW difference between the two scenarios,” Rauch said of the overall resource totals.

“There are some more sensitivities that we’ll run,” Rauch continued. But she said she hasn’t so far noticed anything that would cause MISO to rebuild its assumption from the ground up. She said more testing of MISO’s fleet assumption will likely “help us solidify and refine what comes out of Future 2A.”

WEC Energy Group’s Chris Plante said he was “disappointed” MISO didn’t work with the Monitor to come up with costs for the high gas and battery model to make certain it was what the IMM had in mind.

Minnesota Power’s Tom Butz said MISO’s current generation expansion tool used in modeling, the Electric Generation Expansion Analysis System, is no longer “cutting edge” and can’t capture all nuances of the future grid. He said MISO filled out the hypothetical resource mix with its own predictions when it didn’t see enough generation in members’ plans.

“The bottom line is that this is 100,000 MW beyond what the members have put in there. It’s troubling, and it’s not indicative of a collaborative process,” Butz said of MISO’s forecasted 471 GW.

Drake said MISO plans to move to the more sophisticated PLEXUS tool for transmission planning in the coming years.

Patton questioned why the nearly 30 GW in unnamed, flexible resources MISO prescribed won’t negate the need for some of the hundreds of gigawatts of renewable energy it is also expecting. He said MISO can’t claim it’s planning the most cost-effective portfolio if it’s not siting more battery storage, especially at constrained transmission points.

“It’s not that we lack for capacity. There’s sufficient capacity,” MISO’s Johnson said. Rather, he said, the RTO aimed for a fleet assumption that will furnish energy adequacy across all hours, even in the riskier dawn and dusk periods. MISO foresees a danger of being unable to meet all demand after sunset on hot summer days and during pre-dawn and post-dusk periods on winter days. The RTO said it may find itself depleting battery storage with not enough dispatchable generation to meet hourly demand at those times.

Patton said he thought MISO simply requires capacity under a tougher accreditation to conquer its reliability risks.

Support for MISO’s Fleet Prediction

MidAmerican Energy’s Dehn Stevens said some members’ “myopic view” that the evolution of the system fleet is only going to be driven by capacity needs is “completely off the mark.” He said the race to decarbonize will drive the bulk of the resource transition.

“We think this approach is very good,” Stevens said of Future 2A.

Otter Tail Power’s Stacie Hebert said load growth and resource transformation is imminent for the footprint and that stakeholders need to put more faith in MISO’s expertise in transmission needs.

“It’s easy to pick out things that might not look right from our worldview right now,” she said. But she said MISO is an industry leader in transmission planning. “Inaction and delay also has a cost, so we really need to be balancing our interest in restudies and restudies against inaction.”

“Obviously a lot of the stakeholders expressed frustration today,” Sustainable FERC Project attorney Lauren Azar said. She said she thinks MISO is doing “all of the analysis it needs to do.”

While she said she respects Patton’s opinion on markets, she said he is not a transmission planner and does not specialize in grid planning.

“MISO needs to use its professional judgment about what changes it needs … for the grid in 2042,” Azar said. She said the RTO’s Environmental sector is already concerned that its planning is not keeping pace with the regional backbone projects it will need to support fleet transformation.

“I think we need to move forward and not let the perfect be the enemy of the good,” she said.

IMM Again Expresses Worry for Market Operations

Patton repeated concerns that MISO’s LRTP fleet assumption stands to affect the markets during a mid-September virtual forum hosted by the Gulf Coast Power Association.

The Monitor said that ordinarily, MISO’s transmission planning doesn’t ring alarm bells, but the enormous amounts of renewable energy coupled with “very little” dispatchable generation mean MISO will try to build a transmission system to absorb the fluctuations of an intermittent fleet.

He said “large, uneconomic” transmission investment can dampen the market’s ability to facilitate new generation investment and retirements. It’s imperative that MISO make sure lines address actual needs, he said.

“Now, the reason we care about this is because transmission investments, by definition, occur outside the market,” Patton said. “They’re not being done in response to market signals, and they’re not being paid for through market revenue … and that’s not necessarily bad. That’s a choice that in this country we’ve made in terms of how we make transmission investments.

“But what is important is the investments be made economically … that we invest in transmission as if we were making them in response to forecasted market signals. Because when we make uneconomic transmission investments, then it will distort the market signals and it will adversely affect the participants in the market, as well as raising costs for transmission customers.”

Patton said he envisions “a very different future” by 2040, in which MISO adds 108 GW less in renewable energy than it’s expecting. He maintains that reduction would save the RTO about $120 billion in renewable energy costs by 2040. He said if MISO adopted his view of the future, it would result in more accurate transmission planning.

“What we believe is more realistic is that batteries and hybrid renewables, which have batteries on-site, will be developed,” Patton said.

He also said he takes issue with MISO modeling and planning for a footprint-wide carbon-reduction target when it doesn’t have one.