A new Net Zero Tracker report shows that net-zero pledges among the Forbes Global 2000 has increased 15% since last spring, but the overall picture for corporate pledges is “quite bleak,” Takeshi Kuramochi, a senior climate policy researcher at NewClimate Institute, said Monday.

The companies are concentrated in high-income countries in Europe, North America and East Asia, and the “robustness” of their targets “remains low overall,” Kuramochi said at a press conference in Bonn, Germany, for the release of Net Zero Stocktake 2022.

An assessment of the corporate pledges found that only 35% adhere to the basic pledge criteria set by the U.N.’s Race to Zero initiative. The criteria include specifying a target, taking immediate action, and publishing a plan and progress reports.

In addition, 60% of the pledges do not cover companies’ value chains, while 40% will rely on offsets to achieve the targets.

The findings are “somewhat worrying,” Kuramochi said.

Net Zero Tracker’s report is the first global stock-take released by the team behind the platform since completing a baseline quantitative analysis in March 2021. The platform, which launched in 2019, is a partnership of the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU), NewClimate Institute, Data-Driven EnviroLab and the research initiative Oxford Net Zero at Oxford University.

The tracker is more than a database of net-zero pledges, according to Richard Black, senior associate at ECIU.

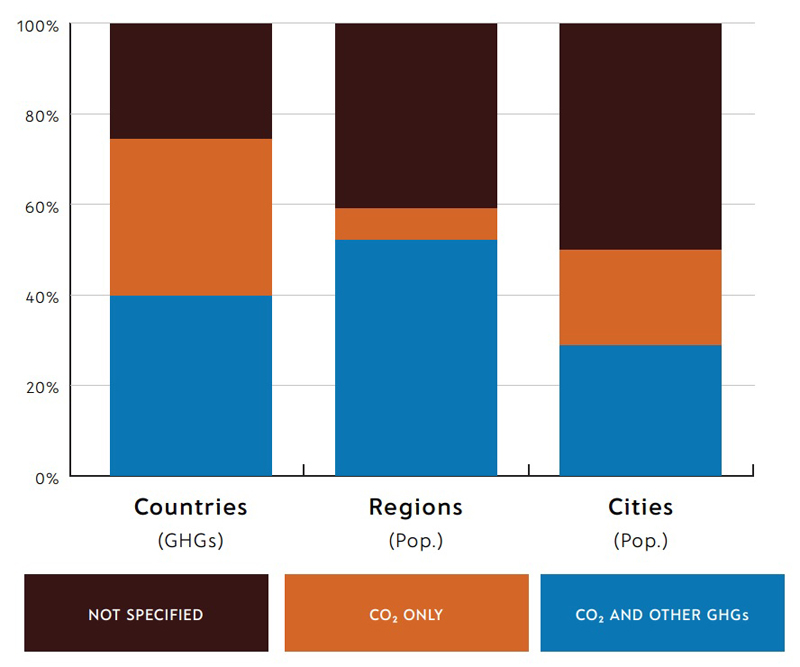

Coverage of greenhouse gases by net zero targets across 128 countries, 235 cities and 115 states and regions worldwide as of June 1, 2022, tracked in terms of GHGs and population covered. | Net Zero Stocktake 2022

Coverage of greenhouse gases by net zero targets across 128 countries, 235 cities and 115 states and regions worldwide as of June 1, 2022, tracked in terms of GHGs and population covered. | Net Zero Stocktake 2022“The days when [the pledge] was the most important metric are long gone; it’s about the integrity of those targets,” he said during the press conference.

To understand the global status of pledges, the database follows 4,000 entities, including all countries; states and regions in the 25 biggest emitting countries; cities with populations over 500,000; and companies on the Forbes 2000. Most of the entities in the database, however, do not have net-zero targets.

For those that do, the research team tracks what entities say publicly about the targets from sources such as speeches, laws, policy documents and sustainability reports.

“We don’t translate this information into temperature projections … or assess compatibility with a 1.5 Celsius global directory,” Black said.

To date, the team has identified 1,180 net-zero targets by countries, subnational regions, cities and companies, up from 769 identified for the baseline report last year.

Kuramochi attributed the increase to new pledges made in the leadup to the U.N.’s 26th Climate Change Conference of the Parties in Glasgow and enhanced data collection methodologies.

Subnationals

The report found that the number of large cities with net-zero targets doubled from 115 in the baseline report to 235, and state and province targets increased from 73 to 115.

While the increase is “encouraging,” the research team wants to see more information available about how those governments will achieve their targets, said Angel Hsu, principal investigator at EnviroLab and an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

“One of the indicators that we look at is whether or not the subnational governments have set an interim target — a midpoint target in route to a longer-term net-zero target — that indicates that they’re thinking about short-term to midterm action and that lends credibility to their implementation plans,” Hsu said.

Of the targets tracked in the database, 40% of cities and 27% of regions do not include interim targets, and about half of the cities and regions have published net-zero plans.

“We also observe a divide in net-zero target setting between Global North and Global South subnational governments,” Hsu said. “The majority of the targets that we were able to record are coming from high-income countries, more than 80% for regions and more than 60% for cities.”

Net-zero Outlook

With the growth of pledges across all segments in the database, the researchers see voluntary pledges changing the regulatory landscape in major economies.

That trend is playing out in several ways, according to Thomas Hale, associate professor of global public policy at the University of Oxford Blavatnik School of Government.

Many voluntary initiatives and pledges, such as the Race to Zero campaign or the Asset Owners Alliance, are working with government leaders to set targets, which Hale said creates the necessary “scrutiny” to ensure governments deliver on climate promises.

High-level climate champions, such as the U.N., are working to set standards and best practices to ensure that there is integrity in the pledges entities make. For example, Hale said that the U.N. secretary-general’s expert group on net-zero commitments will publish a report before the next Conference of the Parties in Egypt in November to “call out the bad, highlighting the good.”

In addition, international standard-setting organizations are working to define net-zero, Hale said. Their efforts will “create mainstream, widely adopted rules for global economic engagement.”

All the momentum around voluntary pledges will build pressure for regulatory changes, where net-zero becomes a baseline for economies, according to Hale. Regulatory progress for net zero is likely to mirror the growth of regulations for how companies disclose climate-related risks, which are in place in the U.K., pending in the EU and Japan, and proposed in the U.S. and China.

“By increasing the quantity, but also critically the quality, of net-zero targets, we’re paving the way for a real realignment of the economy around the goals of the Paris Agreement,” Hale said. The report, he said, “gives us some indicators of who is leading that race and who needs to catch up.”