BROOKLYN, N.Y. — Attendees at the Jan. 11 Offshore Wind Supplier Forum were treated to a precise assessment of what they already knew in varying levels of detail: The young U.S. industry had a difficult time in 2023 and has some growing pains ahead in 2024 and beyond.

BloombergNEF offshore wind analyst Chelsea Jean-Michel said BNEF has reduced its forecast for 2030 installed U.S. offshore wind capacity by 44% due to soaring costs and other struggles.

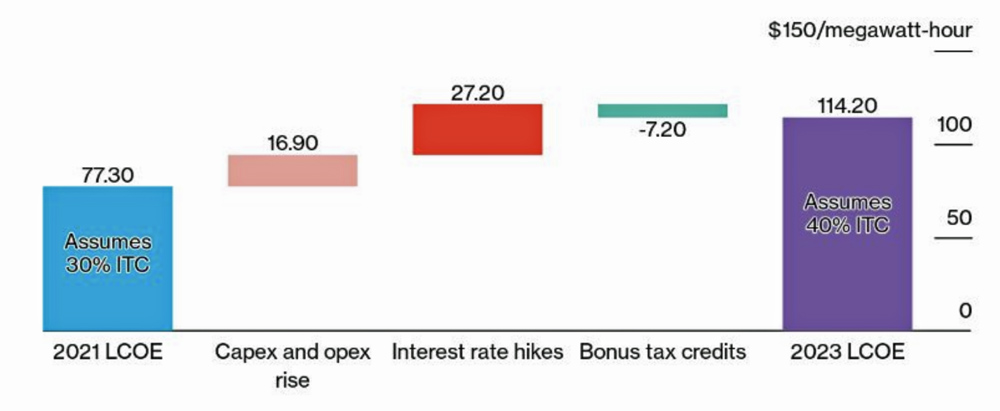

Also, BNEF calculates the levelized cost of electricity for new offshore wind projects at 48% higher in 2023 than in 2021, and that is assuming they qualify for the full 40% investment tax credit, rather than 30%.

And projects totaling more than 12 GW — more than half the U.S. pipeline — have canceled or sought to renegotiate their contracts.

“I hope I haven’t depressed you all too much,” she said to laughter from the room, after 15 minutes of doing just that. “There is so much to be excited for in the industry and so much to be optimistic for. At BNEF we really do view these struggles as a bump in the road, as a sign of growing pains.”

Some of the positives: Only 12% of the pipeline is at the highest risk of cancellation; New York reached provisional contract agreement on three large new offshore proposals even amid all the struggles of 2023; up to 14.8 GW of new contracts could be awarded in five states in 2024; and inflation adjustment mechanisms are being offered in the latest offshore solicitations.

As the offshore wind industry was setting up in the United States, Jean-Michel said, there were some key departures from practices in Europe: States awarded contracts early on in development, rather than later in the process, and compensation was locked in for the life of the contact, rather than with provisions for regular adjustments to reflect rising costs.

Two of the first offshore projects contracted in the United States — Vineyard Wind 1 and South Fork Wind 1 — were far enough along when costs began to skyrocket in 2022 that they could continue to construction. But several others were not. Two offshore farms have been canceled outright before construction, four others have canceled their contracts, and at least three others are at risk of canceling their contracts.

The levelized cost of electricity for all renewables has risen, Jean-Michel said, not just offshore wind.

Onshore wind turbines cost 30% more than they did before the pandemic, she said. It is harder to track the price of offshore turbines because there are fewer such projects and they are less transparent, she added, but “There is reason to believe that offshore wind prices have followed a very similar trend.”

Jean-Michel displayed a chart handicapping 20 nations’ offshore wind goals.

“What’s very telling here is that we don’t think any of these markets are really going to meet their offshore wind targets, except for Taiwan and Poland,” she said. “The U.S. has been hardest hit by some of these macroeconomic pressures.”

Jean-Michel was asked if she thought there would be a true “return to normal” and an end to the financial problems plaguing the offshore industry.

She said it is impossible to predict the future, but governments have adjusted policies to account for financial risk; whether it is enough of an accommodation will start to become apparent soon.

Government support does remain firm at the state and local level. Both states sponsoring Thursday’s forum are bullish on offshore wind as a source of emissions-free energy as well as jobs.

New York and New Jersey are attempting rapid turnarounds after losing three major offshore projects from their portfolios in two months. They are stepping up collaboration with each other to improve the chances of success, and they are continuing to support offshore development with money and policymaking.

Greg Lampman of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority spoke of the scramble underway.

As onshore and offshore renewable projects cancel unprofitable contracts, NYSERDA is racing to get them (or replacements) back in the pipeline at higher costs through new requests for proposals. “Racing” is not overstating the matter — it is a blistering pace by the standards of the regulatory world.

“I’ve got to tell you, I didn’t think we could do it,” Lampman said. “This is moving mountains. Our RFP process typically takes about 14 months. We’re doing it in three.”