MISO juggled several projects over 2023 designed to fend off imminent reliability problems and will keep up the multitasking in 2024.

“I’m still concerned about pace. We still have a lot to do to stay ahead of our reliability issues,” MISO CEO John Bear said during MISO’s final board meeting of the year in December.

However, Bear said MISO accomplished much over 2023, including the largest MISO Transmission Expansion Plan (MTEP) it’s ever produced, a plan to install a sloped demand curve in the capacity auction, work on a future availability-based capacity accreditation for all resources and analyzing the system in preparation for a second cycle of long-range transmission projects.

“Thank you, thank you, stakeholders, for all the work you’ve done this year, and thank you in advance for all the work that you will do in 2024,” Bear said.

Outgoing Organization of MISO States President and Chair of the Michigan Public Service Commission Dan Scripps said MISO has come a long way in the short time since the 2022/23 capacity auction returned a regionwide shortfall in the Midwest.

“Sitting here today, I want to congratulate you on how far we’ve come since last spring,” he told members and directors.

Staff Issue Warnings: 1st Seasonal Auctions Measure up

Despite the grid operator raising alarms over future reliability, MISO’s first four-season capacity auction returned adequate supply, clearing capacity mostly between $2/MW-day and $15/MW-day. (See 1st MISO Seasonal Auctions Yield Adequate Supply, Low Prices.)

MISO conducted the more complex seasonal auction a month later than usual in 2023, impeded by a FERC show-cause order because the RTO incorrectly calculated an unforced capacity-to-intermediate seasonal accredited capacity ratio that it uses to determine supply ahead of the auction.

“The implementation wasn’t completely smooth. There’s always a tradeoff between moving more deliberately and faster, so I’m not particularly worried about that,” MISO Independent Market Monitor David Patton reflected in June on MISO’s seasonal auction.

MISO Executive Director of Resource Planning Scott Wright said the 2022 capacity auction spurred members into adjusting plans that “changed the complexion of the footprint” in the 2023 auction and allowed all zones to meet their reserve targets.

The year ultimately held one maximum generation emergency for MISO at the end of August. (See MISO Calls 1st Summertime Emergency amid Systemwide Heat Wave.)

MISO staff is clear the footprint’s current status as capacity-sufficient is temporary and that thermal plant retirements can be held off for only so long. They spent late spring repeating that the economical capacity prices belied MISO’s mounting resource adequacy risk.

Vice President of Operations Renuka Chatterjee said MISO has a five-year market redefinition plan focused on ensuring its markets can better anticipate growing load uncertainty and output variability.

“Getting to seasonal was so important,” Chatterjee said of MISO’s capacity auction, adding that it’s also valuable to accredit all resources based on when they’re likely to be available over a season.

Last month, MISO reported that over the last five years, its installed wind capacity has increased by 74%, while solar has increased by 1,261%. Combined, MISO’s wind and solar fleet is nearing 30 GW.

MISO’s annual resource adequacy survey in conjunction with the Organization of MISO States this year showed the potential for a 2.1-GW total shortage in the summer of the 2025/26 planning year that could escalate to a 9.5-GW shortfall by the 2028/29 planning year.

Queue Scrutiny

In spite of the RA survey results, the MISO footprint continues to sit on 50 GW of new generation projects that are cleared to connect to the system but are languishing unconstructed. The unrealized gigawatts have added more concern to MISO’s resource adequacy problems. (See “50 GW in Greenlit and Unfinished Projects Haven’t Budged,” MISO Champions Queue Crackdown as Stakeholders Blast MW Cap on Project Entries.)

“Once we get supply chain issues figured out, we’ve got good projects that will make reliability contributions. … But the timing is pretty unclear, when these technologies can be deployed at scale,” Wright told the Advisory Committee at its Sept. 13 meeting.

Fresh Energy’s Mike Schowalter said MISO is on “the tip of the iceberg” in terms of renewable energy and intermittent output. He also predicted distributed energy resources are going to be “bigger than we appreciate.”

At the same meeting, Michigan Public Power Agency’s Tom Weeks said the threat a warming planet presents means MISO members must come up with answers quickly on how to reliably accomplish a decarbonized fleet. He said members of the Advisory Committee should devote meetings to discussing emerging issues.

At last count, MISO’s queue contains more than 1,300 mostly renewable energy projects at nearly 230 GW — or about double its footprint-wide load on a hot summer day. Most of the proposed projects in the study phase of MISO’s interconnection queue are delayed.

“I think looking into the future, the queue is the future. If you want to know what’s coming in 10-15 years, look at the queue,” Wisconsin Commissioner Tyler Huebner said at the September Advisory Committee meeting.

MISO, hoping to cut back on speculative projects in the queue, proposed to establish an annual megawatt cap on projects, enforce stricter proof of land use, enact automatic and escalating monetary penalties for withdrawals, and increase milestone fees for its generator interconnection queue. That filing is awaiting FERC’s approval, with many stakeholders saying there’s no proof a megawatt cap will speed up MISO’s study processing times. (See MISO Champions Queue Crackdown as Stakeholders Blast MW Cap on Project Entries.)

As the holidays came and went, MISO still hasn’t closed its window on accepting proposed generation projects for its 2023 interconnection queue cycle. It said it’s holding off on rounding up new projects until FERC renders a decision on the measures.

“You shouldn’t be in the queue if it’s not your intent to build as soon as you have a [generator interconnection agreement],” MISO’s Andy Witmeier said during the August Planning Advisory Committee meeting.

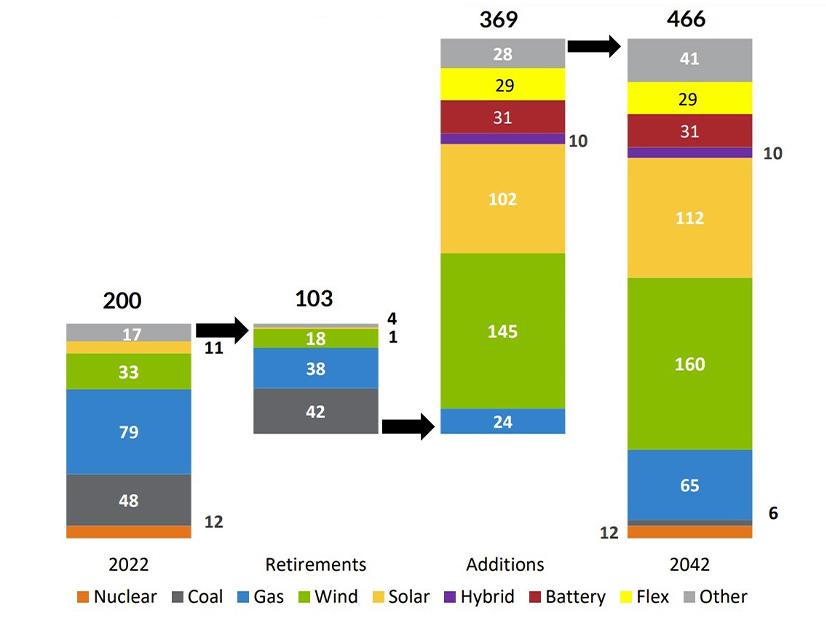

MISO expects members will add 369 GW of new, mostly renewable resources by 2042 and have retired about 103 GW of their existing fleets, bringing the RTO’s total installed capacity to 466 GW. However, only 202 GW of that capacity is assumed to be accredited; staff assumes a declining effective load-carrying capability for the renewable additions. (See MISO: Long-range Tx Needed for 369 GW in Interconnections.) MISO today operates with about 194 GW in nameplate capacity.

MISO similarly is waiting to hear from FERC if it can move ahead with a sloped demand curve in its capacity auction. (See FERC Wants More Detail on MISO Sloped Demand Curve Plan.)

During MISO’s June Board Week, Illinois Commerce Commissioner Michael Carrigan thanked MISO for moving toward a sloped demand curve in its capacity auctions. He said then RTO “cannot ignore portions of the footprint that use different planning approaches,” referring to Illinois’ status as a retail choice state.

“We’ve been in market failure for 20 years because we have a demand curve that doesn’t produce any signals for developers,” Patton said of MISO’s existing vertical demand curve at the beginning of 2023.

New LTRP Portfolio Recommendation

Lastly, MISO is forging ahead with a second long-range transmission (LRTP) portfolio despite a standoff between it and its Independent Market Monitor over their differing visions of the RTO’s resource mix in 20 years. (See IMM Criticizes MISO’s Modeling Software Used for Long-range Tx Planning; MISO Says Overloads and Congestion Loom Without 2nd Long-range Tx Portfolio.)

MISO has said it will reveal line recommendations next year and has emphasized lines will be needed for reliability’s sake to support its members’ energy transition. The RTO is accepting transmission project suggestions from stakeholders.

During a Dec. 6 Advisory Committee meeting, ITC’s Brian Drumm said “rocket fuel” is being poured on the energy transition, requiring major transmission planning of MISO. Drumm told fellow members the “risks of falling behind are much greater” than taking a stab at new line recommendations.

In midyear, MISO proposed a 50/50 split on its third LRTP portfolio, where costs would be allocated 50% regionally and 50% to local zones where the projects are located. The new cost allocation design is tailored specifically to the upcoming transmission projects MISO will recommend for its South region. It’s unclear whether FERC will sanction a separate cost allocation for different LRTP portfolios. So far, Midwestern LRTP projects use a 100% postage stamp to load allocation.

MISO long has said allocation negotiations are a major challenge to raising new transmission towers.

“We can come up with projects, but the allocation is typically the most challenging part of addressing the needs of the fleet evolution,” Vice President of System Planning Aubrey Johnson told board members at a June 13 System Planning Committee meeting.

The grid operator this year also began seriously discussing the possibility of installing HVDC lines to meet broad regional needs. (See Experts Urge MISO to Consider New 765 kV and HVDC Lines.)

In June, Director of Expansion Planning Jeanna Furnish said MISO might consider stringing long-distance, high-voltage lines to allow transfers between load centers like the Twin Cities to St. Louis to Des Moines.

“Staying where we are is not possible. Staying where we are is fraught with [reliability] risks,” Senior Vice President of Planning and Operations Jennifer Curran said at a March board meeting.

“We’ve got 40 million people depending on us for their lives and livelihood, so we have to get this right in this transition,” Bear added.

Bear said the widespread winter storm in December 2022 was in fact a positive because it tested the system, control room and staff. He said it’s important for MISO to be able to test its limits.

“There’s a whole lot in front of us, next year, next year and probably the year after that,” Bear said. “Just in case we get complacent, there’s another extreme weather event every 18 months to keep us on our toes.”